On Writing Biographical Historical Fiction: The Dangerous Lure of Fact

And the frustration of not knowing

A little over a week ago I sent my book coach Susanne Dunlap what we’re calling “The Zero Draft.” That is: the first draft. (Only the first? After all these years!)

It’s the Young Adult novel about Elizabeth Tudor I’ve been researching and writing and moaning about for years. (Writers are boring that way. Q: “What are you working on?” A: “Same old, same old.”)

I believe I’ve now managed to stitch together what I think might be a credible account of this challenging period in young Elizabeth Tudor’s life, but there remains one nugget of hard fact that’s hard to decipher. And, unfortunately, it’s key to her story — her life.

The puzzle

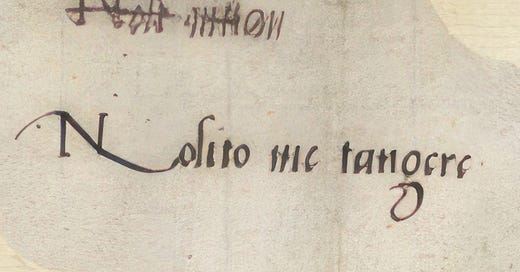

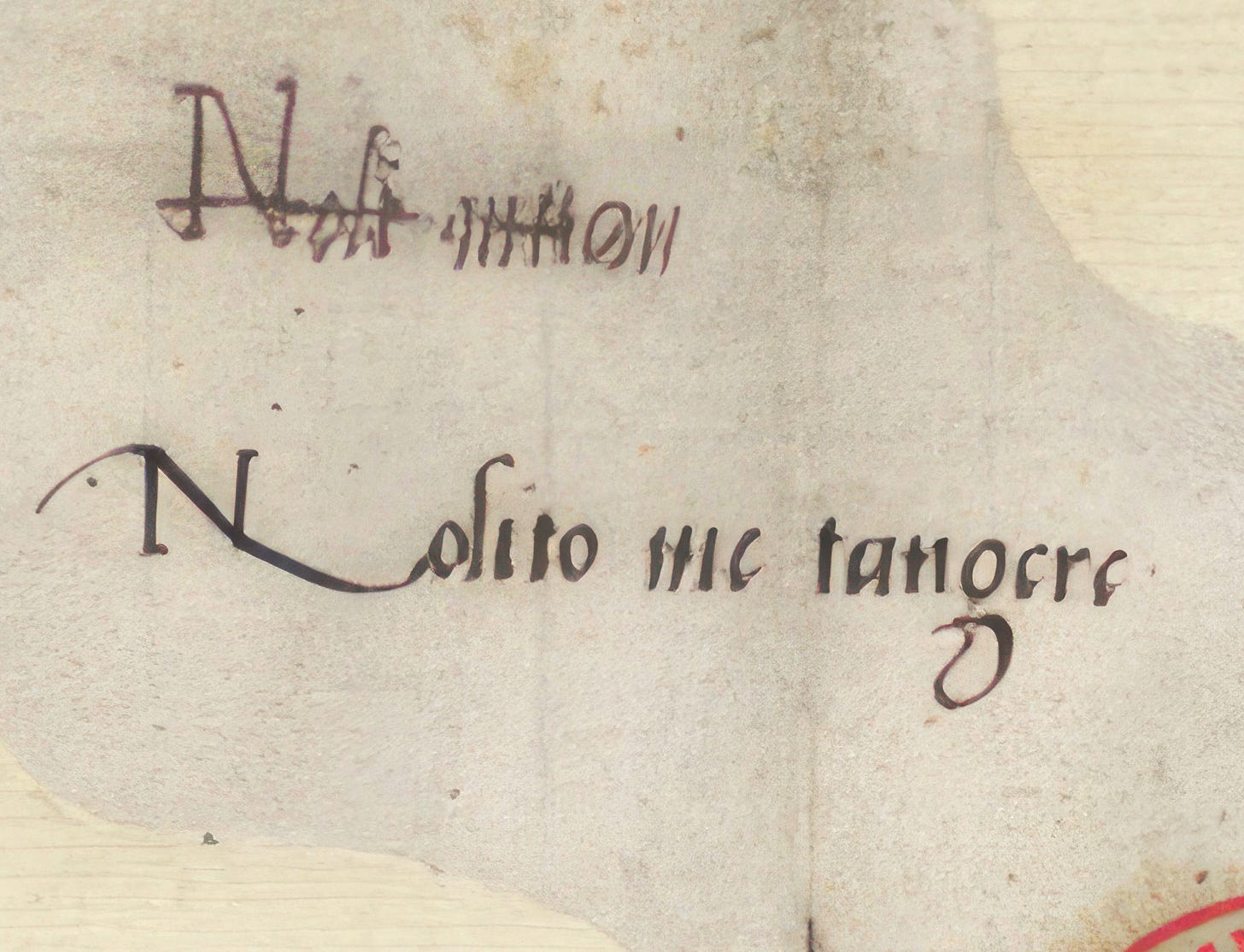

I’ll throw down the fact nugget without context and see what you think. In the image below, do you think the same person wrote both lines?

According to Janel Mueller — a highly-respected Tudor historian whose work I admire greatly — Elizabeth Tudor wrote both lines.1

However, after puzzling over this image, I’m now convinced that the person who wrote:

(misspelling the Latin) is not the same person who wrote:

This second line is clearly the hand of Elizabeth Tudor — but I can’t for the life of me see how she could have written the first line.

Why it matters

This note is written on the back of a letter that Katherine Parr, Elizabeth’s stepmother, wrote to her husband, Sir Thomas Seymour. It’s the only irrefutable document that demonstrates how young Elizabeth might have felt about her stepmother’s overly-friendly husband.

The letter was written on or shortly after June 9, 1548, just before Elizabeth (age 14 and 9 months) leaves her stepmother’s household — either by her own volition or by order of her stepmother. (The common account is that she was sent away.)

Before concluding that Elizabeth did not write both lines, I wrote scenes that accorded with the traditional interpretation. Now I’m thinking of changing all of this, even though it may weaken the novel. (For one thing, who might have written the first line — and why?)

Why change it?

In writing biographical historical fiction, it’s important for me to feel that my fictional account could have been how it happened. It’s a push/pull between accuracy and story, and, without a doubt, the story ultimately rules.

I will likely try changing it and see how it reads. If I decide not to make the change, I could mention the dilemma in the Author’s Note, linking to this post.

Your thoughts?

Long ago, I wrote a number of posts on my WordPress blog on this tricky matter of fact and fiction in biographical fiction. Here are a few:

Frazzled much? The challenges of writing fact-based fiction

The thin (and fuzzy) line between fact and fiction

Also, on Substack:

Mueller, Janel. Katherine Parr; Complete Works & Correspondence, University of Chicago Press, Kindle Edition, footnote on page 169:

Inscription on the verso of the letter, the side bearing the address, in Princess Elizabeth’s hand

Noli metan

Nolito me tangere

Oh these are the historical points on which entire novels can be created. If it wasn’t Elizabeth, who would it be? One of her maids (hence the poor Latin, assuming she had some passing knowledge?) Would there be a ... time difference? Like years passed between the two notations? This is juicy! Good luck! I’m off to check your other essays because sticking to a historical timeline can be really tricky.

The handwriting looks completely different to me.